What do we know about our mental health and addictions system and its performance currently? We know how many hospital beds, psychiatrists, community mental health and addiction agencies there are, and, roughly, the number of people served by these health resources.

What do we know about our mental health and addictions system and its performance currently? We know how many hospital beds, psychiatrists, community mental health and addiction agencies there are, and, roughly, the number of people served by these health resources.

But counting the number of services does not tell us how well the mental health and addictions system is performing. We need much more detailed information about the type of people seeking services, the type of services provided, and the outcomes achieved, or not achieved. Put simply, you cannot improve what you cannot measure.

In December 2013, the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) launched the mental health and addictions research program. It is a program dedicated to using data to generate evidence that can be used to monitor the performance of the mental health and addictions system in Ontario.

Data tells a valuable story

Since the launch of this program, there have been great strides in the understanding of the mental health and addictions system from the perspective of services delivered by physicians, hospitals, and emergency departments. We now know, for example, the regional distribution of psychiatrists, the regional variation of their practice patterns, and the way these two factors interact. This partially explains the challenge people have in accessing psychiatric services.

We have also observed an increase in emergency department visits for mental health and addictions, particularly in transitional-aged youth, and have observed physician follow-up rates after psychiatric hospitalization discharge that are substantially lower than rates for non-psychiatric hospitalizations.

The ICES mental health and addictions program has also been involved in the evaluation of Ontario’s 10-year Mental Health and Addictions Strategy. With the launch of phase two of the strategy, there was recognition of the need for a better approach to mental health and addictions system performance measurement.

As described in Our journey to a data and performance measurement strategy, a collaborative task group with representation from all across the system, including community mental health and addictions, Local Health Integration Networks, and acute-care was created to develop an approach to mental health and addictions system performance measurement that spans the entire continuum of care. This was critical because the work at ICES only provides insight into the services from the acute care (e.g. hospital) sector.

Services provided in the community mental health and addictions sector are substantial but less reported. The reality is that individuals can, and do, receive services from all aspects of the mental health and addictions sector at different points in time.

In order to track performance, though, we need to measure the entire mental health and addictions system, including transitions between the different sectors of the broader continuum of care.

A “major achievement”

The task group created a performance indicator scorecard that represented the entire mental health and addictions system, a first of its kind for Ontario. This was a major achievement.

Previously, hospitals, community mental health and addictions agencies and community support service organizations each monitored performance independently, resulting in different measurement priorities across the system. Furthermore, no standard definitions existed that spanned the sector. For example, the term “wait times” was viewed and measured differently depending on the service provider.

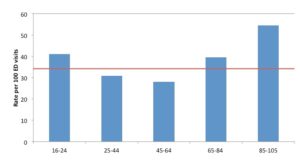

With this scorecard, we can begin to understand some critical information about the mental health and addictions system. For example, Figure 1 reflects adults in Ontario with an unscheduled visit to a hospital emergency department for mental health and/or addictions related reason who also did not have any mental health and/or addictions related outpatient visits, emergency visits or hospital admissions in the past two years.

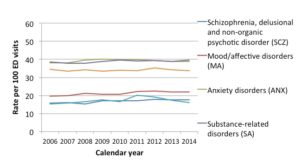

What this indicates is that many clients are having their first interaction with mental health and addictions care through an emergency room. Furthermore, Figure 2 indicates that this type of first contact in the emergency room is more prevalent for certain diagnoses.

The process of developing this system-wide scorecard also revealed the disorganized way in which data is collected and the degree to which the various data sources are disconnected. For example, we are unable to measure whether an individual who has a psychiatric hospitalization is also being provided resources from a community-based addiction or mental health service agency. Put simply, we cannot measure the client journey. Until we can, we are unable to meaningfully comment on performance measurement across the entire mental health and addictions system.

We know that people suffering from mental illnesses and addictions often have difficulty accessing the care they need when they need it. Measurement is a necessary first step in creating opportunities for quality improvement. In the near future, we will be able to say as much about the performance of the mental health and addictions system as other sectors of the health care system. And when we have this capacity, we will then have a mental health and addictions strategy that addresses current gaps and inequities in care so that all Ontarians have access to quality mental health and addictions care at the right time in the right place.

Dr. Paul Kurdyak is a psychiatrist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and Core Senior Scientist and Lead, Mental Health and Addictions Research Program, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, and Co-Chair of the Data and Performance Measurement Task Group of Ontario’s Mental Health and Addictions Leadership Advisory Council.